Discover amazing Free Ebooks and other Resources here

Free

Quality Resources Regularly updated

Get one exciting tri-monthly email update on new products, including new eBooks and coloring pages for your child- designed to spark joy, creativity, and learning in every home!

Click the "subscribe" button below.

The Theory

Handwriting and coloring are essential activities in the development of young learners, with far-reaching benefits for cognitive, emotional, and physical growth. From a psychological standpoint, these activities foster motor skills and brain development. "Handwriting is not merely an academic skill but a fine motor task that affects the brain's sensory processing and motor planning," says Dr. Karin James, a cognitive neuroscientist and professor at Indiana University. Studies have shown that the act of writing by hand stimulates areas of the brain associated with thinking, memory, and learning, as it requires children to engage multiple cognitive functions simultaneously. Psychologist and handwriting expert Dr. Virginia Berninger notes, "Writing activates brain areas responsible for organizing thoughts, which is fundamental to reading and academic success." Moreover, anthropologists emphasize that handwriting and coloring are deeply tied to human evolution, as these fine motor tasks were crucial in the development of tool use and communication. "The act of creating shapes and symbols helped early humans not only communicate but also express identity and emotion," says Dr. John H. Williams, an anthropologist. Contemporary specialists agree that handwriting remains a valuable skill, despite the rise of digital technologies. It is a key element in developing a child's sense of self-regulation, discipline, and cognitive structure. As Dr. Pamela Meier, an expert in early childhood development, explains, "These activities are crucial in helping children understand their environment, express themselves creatively, and develop the foundation for future learning." Thus, handwriting and coloring are far from just playful activities—they are foundational to a child's academic, emotional, and developmental journey.

Insight

Get inspired and help your child discover and learn to write English

Early childhood learning to write in English offers numerous benefits that lay the foundation for a child’s academic and cognitive development. First, it enhances literacy skills by helping children understand the relationship between sounds, letters, and words. As they practice writing, they develop a stronger grasp of spelling, word formation, and sentence structure, which are essential for both reading and writing proficiency.

Writing in early childhood also promotes fine motor skills. As children practice holding a pencil, forming letters, and controlling their hand movements, they develop the fine motor control necessary for tasks such as drawing, typing, and daily activities like buttoning a shirt.

Moreover, early writing encourages creativity and self-expression. Children learn to communicate their thoughts, ideas, and emotions in a structured way, which fosters confidence in their ability to share their voice. Writing also helps with cognitive development by requiring children to think critically, organize their thoughts, and make connections between ideas.

Another significant benefit is social-emotional growth. As children develop their writing abilities, they become more confident in their communication skills, which can positively impact interactions with peers and teachers. Overall, early childhood writing skills serve as a critical building block for future academic success and lifelong learning.

What Are Writing Readiness (Pre-Writing) Skills?

Pre-writing skills are the essential building blocks that children must develop before they can successfully learn to write. These foundational abilities enable a child to grasp and control a pencil, as well as perform tasks such as drawing, writing, copying, and coloring.

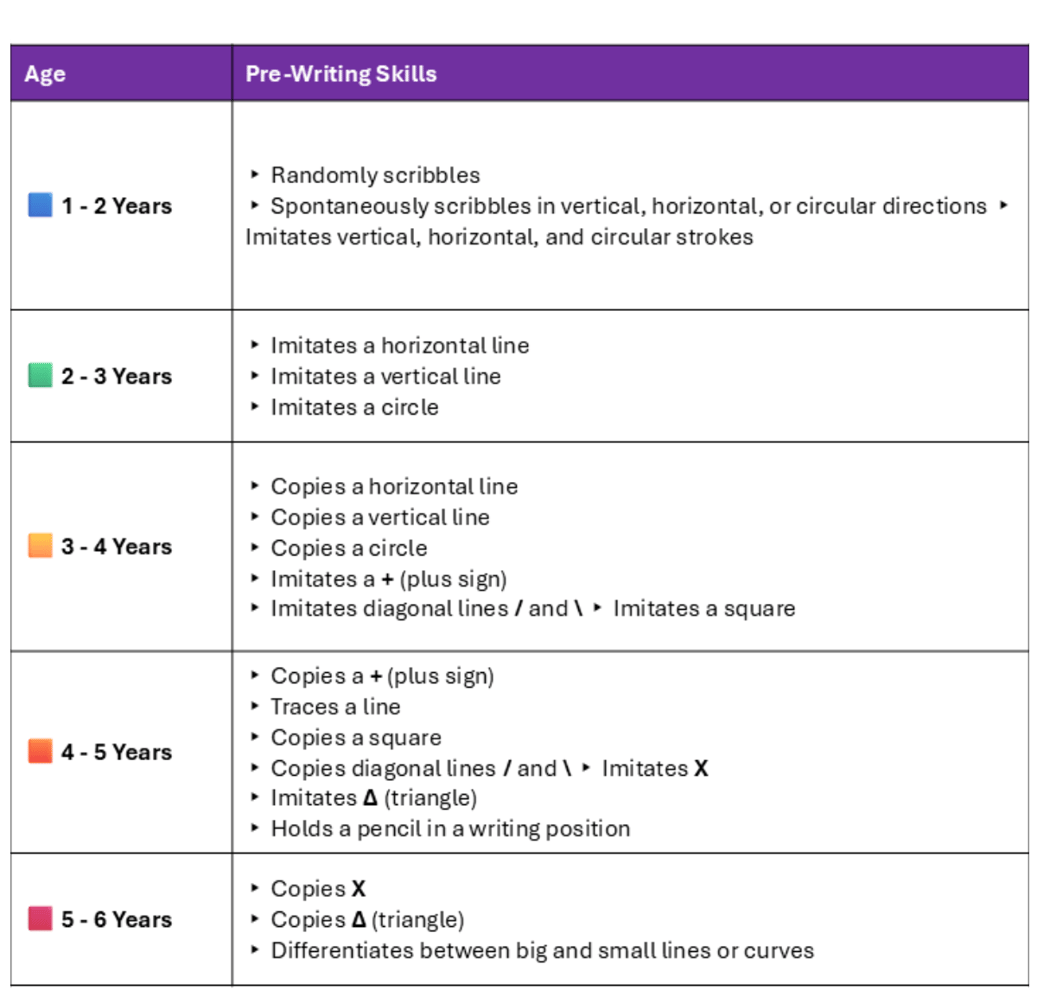

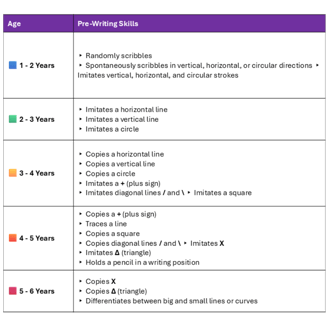

A key aspect of pre-writing skills is mastering pre-writing shapes—fundamental strokes that form the basis of letters, numbers, and early drawings. These shapes are typically learned in a specific sequence that aligns with a child’s developmental stage. The primary strokes include: |, —, O, +, /, □, , X, and Δ.

Why Are Writing Readiness (Pre-Writing) Skills Important?

Pre-writing skills are crucial for helping children develop the control and coordination needed to hold and maneuver a pencil smoothly and efficiently, ultimately leading to clear and legible handwriting. When these foundational skills are not well-developed, children may struggle with writing tasks, leading to frustration and reluctance.

Difficulties in writing can result in slower progress, fatigue, and an inability to keep up with classroom activities, which may negatively impact a child’s confidence and academic performance. Strengthening pre-writing skills early on sets the stage for a more positive and successful learning experience.

What Are the Essential Building Blocks for Writing Readiness (Pre-Writing)?

To develop strong writing readiness skills, children need to build a foundation of essential motor and cognitive abilities. These key building blocks include:

Hand and Finger Strength – The ability to apply controlled force using the hands and fingers, providing the muscle power needed for precise pencil movements.

Crossing the Midline – The ability to move a hand or foot across the body’s centerline (an imaginary line running from nose to pelvis), which is essential for fluid and coordinated movements.

Pencil Grasp – The ability to hold a pencil in a way that supports age-appropriate control and movement.

Hand-Eye Coordination – The capacity to process visual information and translate it into controlled hand movements, crucial for tasks like handwriting.

Bilateral Integration – The ability to use both hands together in a coordinated way, such as holding the paper steady with one hand while writing with the other.

Upper Body Strength – The stability and strength in the shoulders and upper arms that allow controlled, sustained hand movements for writing.

Object Manipulation – The skill to efficiently handle and control objects, including pencils, scissors, and everyday tools like cutlery or a toothbrush.

Visual Perception – The brain’s ability to interpret and understand what the eyes see, which is critical for recognizing letters, numbers, and spatial relationships.

Hand Dominance – The consistent use of one hand (typically the same hand) for fine motor tasks, allowing for more refined motor skill development.

Hand Division – The ability to use the thumb, index, and middle finger for fine motor control while keeping the ring and little finger tucked into the palm for stability.

Developing these foundational skills is essential for a child to write with ease, confidence, and efficiency.

How Can I Tell if My Child Has Difficulties with Writing Readiness (Pre-Writing) Skills?

If a child struggles with writing readiness, they may exhibit the following signs:

Awkward Pencil Grasp – Holding a pencil in an inefficient or uncomfortable manner.

Difficulty Controlling a Pencil – Struggling with tasks like coloring, drawing, or writing.

Using the Whole Hand for Manipulation – Relying on the entire hand instead of just the fingers to manipulate small objects.

Low Endurance for Pencil-Based Tasks – Becoming easily fatigued when engaging in writing or drawing activities.

Messy or Slow Handwriting – Writing that is difficult to read or takes significantly longer than expected.

Trouble Staying Within Lines – Struggling to keep coloring or writing neatly within boundaries.

Inconsistent Pencil Pressure – Pressing too hard (frequently breaking the pencil) or too lightly (producing faint, shaky lines).

Weak Upper Limb Strength – Poor shoulder stability, making controlled hand movements challenging.

Difficulty with Bilateral Coordination – Struggling to use both hands together effectively, such as holding the paper steady while writing.

Poor Hand-Eye Coordination – Trouble aligning hand movements with visual input.

Strong Verbal Skills but Weak Written Output – Expressing ideas well verbally but struggling to convey them through writing, drawing, or coloring.

Not Meeting Age-Appropriate Pre-Writing Milestones – Falling behind in expected pre-writing skill development.

If several of these challenges are present, your child may benefit from targeted activities to strengthen their pre-writing skills and build confidence in early writing tasks.

What Makes Play Essential?

Understanding Play

Play is a dynamic, multifaceted, and intricate concept that resists simple definition. It is widely recognized as a universal activity, with children often regarded as naturally inclined to engage in play.

Scholars define play as an activity that exhibits the following characteristics:

Deep Engagement and Focus – Play involves high levels of absorption, active participation, and intrinsic motivation.

Creativity and Imagination – It is often imaginative, symbolic, and non-literal in nature.

Autonomy and Freedom – Play is voluntary, self-directed (frequently initiated by children), and operates without externally imposed rules.

Structured Yet Flexible – While fluid and dynamic, play is also guided by internal mental frameworks, including high levels of self-awareness and communication about communication (metacommunication).

Process-Oriented – Play is driven by exploration and experience rather than by external objectives or tangible outcomes.

By fostering creativity, problem-solving, and social interaction, play serves as a fundamental component of human development.

The Various Forms and Structures of Play

Play manifests in diverse forms, often overlapping within a single play experience. Common categories include:

Exploratory Play – Engaging with objects to investigate and understand their properties.

Physical Play – Activities that involve movement and coordination.

Pretend, Fantasy, and Dramatic Play – Role-playing and imaginative scenarios.

Games and Puzzles – Activities that incorporate rules, strategy, and problem-solving.

Constructive Play – Creative endeavors such as artistic expression and musical exploration.

Language Play – Experimenting with words, rhymes, and linguistic structures.

Outdoor Play – Interaction with natural environments, often involving physical activity.

Understanding Free Play

Free play refers to play that is initiated and directed by children, allowing them to independently choose activities, explore their surroundings, and engage in open-ended interactions. This form of play fosters creativity, self-expression, and autonomy, as children determine the focus and direction of their play without adult interference.

However, free play is not entirely without external influences. While children shape their own experiences, the play environment—structured by adults through physical space, rules, and available materials—can subtly guide their choices. Additionally, factors such as gender, cultural background, socioeconomic status, and physical ability may influence how and with whom children engage in play. Some scholars argue that these external factors raise questions about whether free play is ever truly unrestricted. Despite these considerations, free play remains a vital component of childhood development, encouraging independence, problem-solving, and social interaction.

The Developmental Progression of Play

As children grow, their play becomes more intricate, requiring increasingly advanced social, cognitive, and physical skills. While all children engage in various types of play, certain forms are more prevalent at different developmental stages.

Infants and Toddlers – In the earliest years, children primarily engage in exploratory and social play, such as games like peek-a-boo. Exploration serves as a foundation for play, helping children gather information about their environment. Toddlers begin to participate in functional play, which involves repetitive physical actions, as well as early forms of pretend play.

Preschool and Early Childhood – As children’s imaginative abilities expand, they engage more frequently in constructive play, pretend play, and language play. During this stage, they develop stronger problem-solving skills, richer language use, and greater capacity for collaboration. Their activities become more structured, intentional, and goal-oriented, with an increasing ability to manipulate and combine materials in complex ways.

Sociodramatic Play – Around ages 4 to 5, children begin participating in sociodramatic play, which involves cooperative role-playing and the coordination of shared narratives with peers. This type of play is cognitively demanding, requiring children to simultaneously manage multiple aspects of the experience—negotiating roles, maintaining character perspectives, following agreed-upon storylines, and assigning symbolic meaning to objects.

Through these progressive stages, play not only reflects but actively supports children’s growing cognitive, linguistic, and social development.

The Role of Play in Effective Learning

Research on the relationship between play and learning is complex due to varying definitions of play, the overlap between play types, and external influences such as environment and adult involvement. Play is a multifaceted activity with interconnected dimensions, making it difficult to isolate its direct impact on learning. Some researchers suggest that learning gains associated with play may stem from specific adult interactions or structured content rather than play itself.

Current evidence does not definitively establish whether play is essential for development, whether it is simply one of several effective learning methods, or whether other underlying abilities—such as social intelligence or language skills—are the true drivers of learning. Additionally, many studies on play and learning suffer from methodological limitations, small and homogeneous samples, and inconsistent findings, leading to conflicting recommendations for practice.

However, despite these challenges, a substantial body of research suggests that play is a powerful and integral mode of learning. Through play, children integrate experiences, construct knowledge, and make sense of the world around them. Pretend play, for example, fosters the ability to think abstractly—an essential skill in both learning and everyday life. The benefits of play extend across multiple developmental domains, including:

Well-Being and Motivation – Play promotes self-efficacy, intrinsic motivation, and a positive attitude toward learning environments, including early childhood settings and schools.

Cognitive and Academic Development – Play enhances exploratory thinking, abstract reasoning, communication skills, creativity, and literacy and numeracy abilities. It also strengthens self-regulation, executive function (such as impulse control and working memory), metacognition, and problem-solving skills.

Social and Emotional Growth – Play supports the development of social skills, including making friends, expressing emotions, resolving conflicts, and fostering empathy. It also helps build resilience.

Physical Development – Play contributes to motor skill development and strengthens both fine and gross motor coordination. Physical play, in particular, has been linked to improved cognitive function, behavioral regulation, and academic achievement.

While research continues to explore the nuances of how play influences learning, the evidence strongly suggests that play serves as a valuable tool for cognitive, social, emotional, and physical development.